It’s no secret that Facebook is sold to us as the lovechild of globalisation and innovation. It’s heralded across the Western world as a way to bring together businesses and buddies, countries and cultures into a participatory and egalitarian community. Zuckerberg is seen as a modern-day wizard genius extraordinaire, and in many ways Facebook is talked about as though it’s synonymous with the entirety of the Internet itself (as we saw earlier this week when the ‘Internet’ was brought down by an error in Facebook’s Connect code).

But just how much of this is actually true? I mean, maybe we’ve just fallen for Facebook’s clever marketing. Or maybe its marketers were helped along by the fact that Facebook itself fits seamlessly into a preconceived idea we’ve all grown up with, a sort of self-advertising narrative of progress through globalisation. Either way the question stands, just how does Facebook bring the world together?

The picture below was compiled by Facebook engineer Paul Butler way back in 2010, and it fits into this narrative like a final jigsaw piece. Each line represents a relationship between two people – the brighter an area the more concentrated those online relationships. It’s truly breathtaking.

Thousands of images just like this one are presented to us daily as a form of documentary reinforcement for the triumph of globalisation, a fact many of us wouldn’t second-guess. But when we take a critical step back from our discourse, you can’t help but notice a very different picture hiding inside this one.

All you have to do is stop looking at the faint blue lines and instead concentrate on the vast empty spaces between them.

Notice specifically the giant black holes in Central and Northern Africa, Russia, the Middle East, Central Asia, China and Oceania. If this image shows the extent of Facebook’s reach, there’s a significant portion of the world which isn’t represented here. And of the relationships Facebook facilitates, the majority of them are remarkably insular, occurring intensely within a country but less so outside its borders and immediate region.

It’s a peculiar pattern supported by this highly-recommended data visualisation published by Facebook Stories last year. Almost every country you click on, the largest bubbles are of its immediate neighbours, with the sort of exceptions you’d expect (Spain-Latin America, UK-Australia-India etc.). Most of these links are remnants of a pre-Internet age, from things like European colonialism and post-WW2 migration – but as for any new, radical, quirky or novel cross-cultural exchanges, there just isn’t the volume you’d anticipate. This isn’t the profile of a vast, interconnected network – it’s more like a chain, or a series circuit.

A lot of this is explicable by what media theorist Joseph Straubhaar has called cultural proximity, “the tendency to prefer media products from one’s own culture or the most similar possible culture” (2003, 85). Because of this Straubhaar notes the formation of certain media markets and that:

These markets might more accurately be called cultural-linguistic or geocultural markets rather than regional markets because not all these linked populations, markets, and cultures are geographically contagious.” (2007, 171)

For the most part though, voices like Straubhaar’s haven’t been absorbed by the zeitgeist. Instead, talk and images of how Facebook is the ultimate global village cum democratic network, how we are all connected, how a combination of the Internet and technology will save us all, and so on, can leave us with a compromised image of the actual world around us which systematically under-represents the majority of humanity and overstates the role of the Internet.

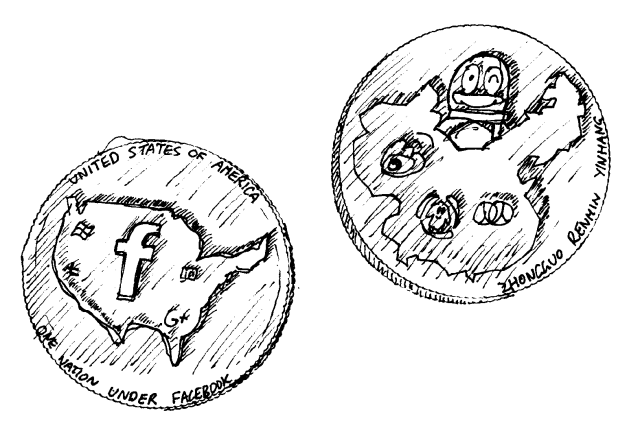

We’re often reminded that Facebook, if it were a country, would have the third largest population on the planet, with something like 1 billion active monthly users. That sounds impressive on paper – until you remember that this means 85.7% of the world’s population is NOT on Facebook.

This isn’t the way it’s talked about though – Facebook is touted as being synonymous with the Internet itself. But looking at these figures, this would be like saying the entire world was Hindu.

What’s more, the minority which is on Facebook isn’t spread evenly across the world. About one in two people in the US use Facebook, giving it the highest number of national users. Brazil comes in second with one in three. India comes in third with almost 63 million users, but this is only 5% of India’s population.You can’t look at the volume of users alone and conclude that Facebook has reached the same level of cultural penetration abroad as it has in the US, now effectively one nation under Facebook – yet you’d be forgiven for thinking that it has.

To see more of how global Facebook users are distributed check it out here.

At this point, it’s sobering to remember that the Internet is not as far-reaching as we’d imagine. Only a third of the world is online. It’s weird to think, given how self-propagating it is, for a discursive two-thirds of the world’s population the Internet is largely non-existent. In fact, graphics like the one above compel us to paint a portrait of the Internet which is drastically lopsided.

For example, most of the websites on the Internet are in English (about 57%), but you’d be mistaken to think that 57% of Internet users come from English-speaking countries. I know – that’s just logical, yet this seems to be the prevailing belief. In reality, the number of Internet users in China dwarfs the number of those in the US by more than double. India, Japan and Brazil follow respectively.

Of the top 20 countries sorted by the number of Internet users, only 3 are officially English speaking. (source)

It’s when you see statistics like this that you realise our rhetoric is wrong and talk is cheap. We talk about ‘the West’ and ‘the Third World’, and a divide between the developed/developing world, but in light of honest inquiry these terms can’t help but seem condescending – and more fundamentally – inaccurate.

Undoubtedly Facebook seems all-pervasive and unavoidable. But when we take a step back and look at the bigger picture, it turns out that Facebook is used by the minority of the minority of the world, about a third of a third (1 billion users). That’s significant yes, but on equal footing with (if not slightly below) the combined cultural force of Chinese microblogging and social networking platforms QQ (712 million users), Qzone (>400 million, part of the QQ network) and Weibo (>300 million). This is a side of the coin we’re rarely presented with – and if we are, it’s downplayed.

The closer you look, the more it seems that the Internet is not one unified, globally aware cultural force, but that there are in fact many different Internets separated by cultural proximities that rarely come in contact with one another. The Internet looks very different to many different people. Commentators refer to this phenomenon (although with slightly different connotations) as cyberbalkanisation, or my personal favourite, the splinternet.

There’s a disparity here between reality and what we perceive. And this should be alarming – especially when so much of discourse is weighted toward the antipodal, dreamy-eyed vision of globalisation – because it gives us a false impression of the world around us. It seems to pander the minority, and seems to value their role in shaping global discourse disproportionately. And it compels us to whitewash the globe with a narrative of all-inclusive connectivity which can only ever be understood as progressive, regardless of the truth.

Graphics like Butler’s are elegant but ultimately deceptive, and they tend to oversell the unifying power of Facebook (and more broadly the Internet) in our modern world. As an analogy, Facebook increases the sensor size without increasing the megapixels – we’re given a bigger picture but with no greater resolution.

If anything I hope this post helps us avoid tripping into the pitfall of conflating what occurs on Facebook at a local level with what’s happening on the global level, and encourages a humbler inspection of the true breadth and depth of globalisation.

But what do you think? Does the discourse surrounding Facebook enrich our global consciousness and work toward world peace? Or does it give us a more parochial and pixelated view of the world?

Looking forward to seeing your thoughts.

Cheers,

Mark

Pingback: Does Facebook bring us closer? | We Are Not Connected

Given the various privacy issues, and paranoia about identity-theft, FB is geared towards being localised, as most people would prefer to be safe in what information they disclose about themselves, especially if you are from a country, where at anytime even the most harmless information can be used against you.

Our world is driven by greed, covetousness and competition, and conflicts arise, because how I want to order my world would differ from how you want to order your world. My vision for world peace would be different from yours, and I dont see that kind of meaningful dialogue taking place on FB where ideas are shared and wheat separated from the chaff.

There is far more that needs to change before there can be world peace – not just the absence of conflict, but more than that – a wholeness and wellness, where there is no injustice or violence and there is true equality… FB and blogs can stir up thinking but can they really bring about lasting change in heart attitudes… I dont know…

I suppose I was being tongue-in-cheek when I mentioned world peace, but you make a good point nonetheless.

Equality and respect are definitely the way forward. Realistically though, I’ve no idea what that would mean/look like, and I acknowledge that this just isn’t going to happen, at least not for hundreds of years.

If anything, I think a step in the right direction would be through increased global commerce and trade. Mutual investment in one another’s wealth, productivity, welfare, security and future is surely one of the greatest signs of respect and empathy human beings can give to one another, both on a local and global level.

The healthy bidirectional exchange of goods, services, or ideas is perhaps the most peaceful thing we’re capable of.

Anyway, thanks for your comment

Yeah, Facebook is where we all get together and sing Kumbayah, except that it’s politically incorrect to sing Kumbayah (old spiritual, don’t you know). And if you want to post something that doesn’t fit into the Leftist narrative, hey, you get reported or blocked or somehow shut up.

I got out of the metaphorical tarpit that is facebook last summer. I missed it for about a week. It’s a powerful addiction. People are breaking it, though.

Zuck may find that being a cyber tyrant is not a good business model.

I think we’re mixing terms here. When I refer to ‘democratic’ I’m not referring to democratic/republic. I mean it in the colloquial sense of the word as egalitarian.

As for leftist agendas or cybertyranny, I’m not so sure. I think this stranglehold is ultimately an illusion. It might be the case locally in specific parts of the US, but not globally. Thanks for your comment

I have a hard time wrapping my own mind around the fact that you can write like this and draw! Love it!

You hit on a lot of great points. I have friends all over the world from blogging and welcome them to follow me on Facebook. The world becomes so much smaller and we see our similarities more than our differences.

Thanks Susie, I can only say the same about you though!

You are too nice, but thank you!

I don’t have a Facebook account and I don’t really care to. I think it is the hype that makes you think you NEED to be on Facebook. I am hoping that it is a fad that will move from the personal connections that consume it today, to a more business oriented thing.

It probably feels otherwise but at this moment, only half of Americans use FB, so you’re part of a big group!

I wholeheartedly agree with you, Facebook is definitely moving toward a consumer-company network, I’m going to write about this next about Facebook. Stay tuned!

Pingback: America Online: Loss of American Culture to the Global Internet | Staci Morrison 2.0

Interesting point about looking ‘past the blue lines’ to the empty dark holes in the so-called network. We have evolved a lot of graphing / visualization methods of late and it’s interesting to see that they can bias you toward the preferred insights just as much as raw stats (e.g. reported in a news article) or plain ‘ole bar charts with suspicious (eg unlabelled) scales. Wrt facebook I’ve always thought it highly overrated but that overration never stopped anything in it’s tracks before :o)

Thanks for your comment Leona. It reminds me of something written by Edward Said in ‘Orientalism’:

“… the real issue is whether indeed there can be a true representation of anything, or whether any and all representations, because they are representations, are embedded first in language and then in the culture, institutions, and political ambience of the representer. If the latter alternative is the correct one (as I believe it is), then we must be prepared to accept the fact that representation is eo ipso implicated, intertwined, embedded, interwoven with a great many things besides the “truth,” which is itself a representation.” (1978, 272)

Seems to ring true across the board, especially when we conceive of grand conceptual processes like ‘globalisation’ (as though it’s a recent phenomenon), and how technologies like Facebook, and the graphs and other visualisations which tangent off of them, can easily represent themselves in terms of that preexisting narrative, regardless of its acultural, apolitical or otherwise objective value.

Got pretty deep there, but thanks again for your thought-provoking comment lol. Might do a whole post on Said…

Pingback: What is the globe? | We Are Not Connected